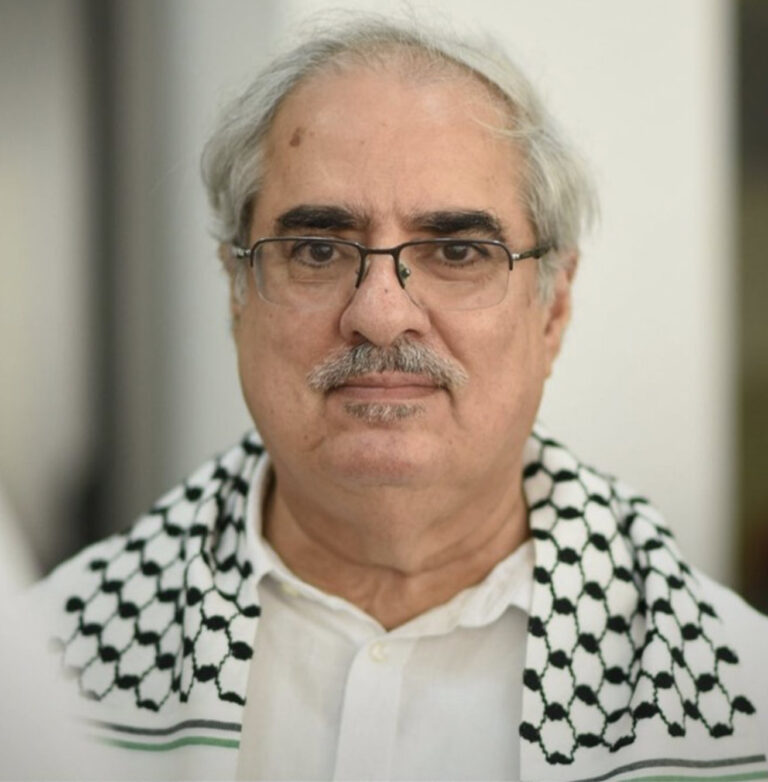

10 September 2018 – Bahrain’s Ministry of Interior Ombudsman’s Office – the chief oversight mechanism for the police and prison system – released its findings on 7 September concerning the case of imprisoned political leader Hassan Mushaima. The Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD) says the results of the Ombudsman’s investigations are largely misleading and inaccurate. Not only do they suggest that Mushaima wanted to violate the law and regulations of the prison or be granted exceptional rights, but they fail to acknowledge continued violations of international detention standards within Bahrain’s Jau Prison.

It is important to note that while this statement covers access to basic prisoner rights as per international standards, prisoners of conscience like Hassan Mushaima should not be incarcerated to begin with. Mushaima and others were subjected to torture, forced to sign confessions, denied access to due process, and sentenced to life, based on practicing their right to freedom of expression. Mushaima and all other prisoners of conscience in Bahrain must be released immediately and unconditionally.

Denial of Adequate Medical Care

The Ombudsman’s report acknowledges that Mushaima, a leading opposition figure sentenced to life in prison for his role in the 2011 pro-democracy movement, was prevented from accessing adequate healthcare for his serious medical conditions including erratic blood pressure, gout, diabetes, and cancer (currently in remission): “The Ombudsman’s investigation independently established that it was the case that Mr Mushaima had not been permitted to leave Jau rehabilitation Centre to attend medical appointments in external hospitals.” As the Ombudsman admits, this stems from Mushaima’s refusal to submit to unlawful and humiliating restrictions on access to medical care imposed on Jau prisoners, including shackling and strip-searches. He has so far only been able to receive medical care on an “exceptional basis” from this restriction, which, according to the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (also known as the Mandela Rules), amounts to ill-treatment. Despite this admission, the Ombudsman entirely failed to acknowledge that this policy contravenes international standards and is, therefore, the root cause of the problem. Furthermore, it fails to address the fact that this exception was only made amid international scrutiny of the abusive restrictions following his son Ali’s decision to launch a hunger strike in protest of the mistreatment outside the Bahrain embassy in London.

Moreover, the Ombudsman declines to acknowledge that Mushaima was advised to see a diabetes specialist in January 2018 and yet was denied follow-up appointments by Jau prison authorities. Instead, they continue to provide Mushaima only with temporary medication that is meant to stabilise his blood sugar until he can see a diabetes specialist. BIRD understands that neither the Ombudsman nor the prison authorities have made progress in arranging this appointment.

Denial of Family Visits

As with medical care, Jau authorities deny inmates the right to family visits unless they submit to humiliating shackling and strip-searches in contravention to international standards. The Ombudsman’s investigation inaccurately attributed the prison’s denial of Mushaima’s visitation rights to his refusal to accept the number of hours with visiting family, rather than his rejection of arbitrary restrictions designed to degrade prisoners of conscience. BIRD has obtained a phone call recording in which Mushaima clearly states that his main objection is the humiliation imposed by these new restrictions, which he finds insulting and in violation of the Mandela Rules, in contrast with the Ombudsman’s position that they are “culturally sensitive, proportionate and respectful of human dignity.” The Ombudsman additionally failed to note that these restrictions are not longstanding policy, but were arbitrarily imposed in February 2017 as another means of collective punishment and reprisal against prisoners of conscience.

The Ombudsman must ensure that Hassan Mushaima and his fellow inmates are all granted two hours per month, that is an hour every second week, without being subjected to humiliating measures (e.g. strip searches).

Confiscation of Books and Personal Items

Lastly, the Ombudsman’s investigation failed to explain why Mushaima’s books and personal items were confiscated in October 2017. Mushaima has requested at least four times that his books be returned, and yet, a week ago he received contradictory information from the prison regarding their whereabouts. It is unclear whether they have been destroyed or relocated. The Ombudsman’s findings additionally make no mention of Mushaima’s personal and handwritten papers which were also confiscated. Moreover, the policy itself is unclear and arbitrary, as inmates repeatedly report delays and unexplained rejections of books provided by family members. The Ombudsman asserts that all confiscated books were returned to Mushaima’s family, but this is false.

The Ombudsman further failed to mention that the Jau Prison administration made an agreement with the Bahrain 13 opposition leaders and activists back in 2012, which allowed prisoners to have more than two books at a time (under official prison regulations prisoners with access to prison libraries are allowed two books at a time that they can exchange once completed). The Jau Prison administration had to compensate for denying the prisoners access to a prison library, a basic right afforded to prisoners and available in all other prison buildings. Mushaima and the other prisoners have had access to several books for the past six years, which they would receive after approval by the prison administration. Mushaima’s collection of more than 100 books remains in accordance with this agreement, and the confiscation of these books by prison authorities in October 2017 was in violation of the agreement, completely arbitrary and imposed solely as an additional punitive measure.

Inconsistencies Between the Arabic and the English Version of the Statement

The English and Arabic Versions of the Ombudsman’s Statement present some inconsistencies. The English version administers softer language which suggests cooperation and good faith on part of both the Prison Administration and the Ombudsman.

For instance, the English version of the statement, states: “the Ombudsman Office requested the rehabilitation centre administration to, on an exceptional basis, permit Mr Mushaima to attend an outside hospital consultation for a health check-up without being handcuffed”, and that the prison administration “responded cooperatively” stating that “they would make the necessary arrangements to escort Mr Mushaima to hospital without requiring him to be handcuffed”. This request was forwarded by the Ombudsman because they took into account “Mr Mushaima’s age and medical history”. However, the Arabic version has a slightly different connotation. It says that the Ombudsman recommended that the prison administration allow Mushaima “one exceptional time” to attend his medical examination in the external hospital without being handcuffed “to verify the allegations about his health”.

Other Omissions

Throughout its report, the Ombudsman refuses to address the core issue: what steps is their office taking to ensure that an elderly prisoner that poses no escape risk is not subjected to degrading and humiliating restrictions in violation of the Mandela Rules and which endanger his access to necessary healthcare? The Ombudsman must initiate an investigation into these abusive policies – rather than accept intermittent “exceptions” – and guarantee that he is provided all required medical treatment and family visitation without constraints. It must additionally ensure that all of Mushaima’s books are given back to his family, if they are not returned to him, and take measures to prevent prison authorities from confiscating books arbitrarily.

The UK training to Bahrain’s oversight bodies

Since 2012, the FCO has spent more than £5 million on its technical assistance programme to the Kingdom of Bahrain to train Bahrain’s police and prison guards on human rights and establish new bodies to investigate torture allegations. The Ombudsman and Special Investigation Unit (SIU), both recipients of the FCO’s technical assistance programme and mandated to investigate human rights abuses, have instead covered-up serious claims pertaining to torture alleged by death row inmates, thereby allowing their trials to rely on coerced confessions. Meanwhile, the National Institute of Human Rights (NIHR) has publicly endorsed executions and claimed that torture does not occur in detention facilities, despite the numerous inmates who have alleged the opposite. The severity of the failures has attracted significant international criticism, with the UN describing these institutions as ‘not independent’ and ineffective in both 2017 and 2018.

On Tuesday 11 September, a Westminster Hall debate will discuss the failures of UK-trained oversight bodies in Bahrain, such as the Ombudsman, and the deteriorating human rights climate in the country.