8 March 2019 – Three Bahraini women political prisoners wrote to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, earlier this year, to request her intervention in their case.

Hajer Mansoor Hassan, convicted in reprisal for the activism of her son-in-law, Najah Yusuf, tortured and sexually abused for her criticism of the Formula One Grand Prix, and Medina Ali, also arrested, beaten and convicted over politicised charges, are all serving three years in prison following deeply flawed trials.

The three recounted their ordeals suffered at the hands of the Bahraini authorities “in an era where the world is especially attuned to hearing the ordeal suffered by women”. They also exposed the worsening prison conditions in Isa Town Prison, including punitive measures which they claim are designed to “break [them]”.

The women have not seen their families since September 2018, when they were assaulted by prison guards in response to the international attention they received at the UN and UK government. A glass-barrier has been imposed in the visitation room, which the women refuse to accept. “It would break our hearts to see our children behind a glass barrier and not be able to hug them”, they said, “We cannot accept to see our elderly parents, some of whom are bound to a wheelchair, in distress, without being able to offer them comfort nor solace.”

Since the beginning of the year, the three women have also been denied access to urgent medical care. Hajer, in particular, was refused access to examination for a lump in her breast which prompted an “Urgent Action” by Amnesty International.

They appealed to the High Commissioner to “speak out” and “act on [their] behalf” to secure their release.

Full letter below:

Dear Michelle Bachelet,

We are three Bahraini women who have been incarcerated by our corrupt justice system, for it believes that freedom of expression is a crime. As the new year begins, we express ourselves openly and honestly in an era where the world is especially attuned to hearing the ordeal suffered by women.

We were moved by your appointment as the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in September, as you, too, have felt the brutality of a dictatorship first hand. Each of us has been subjected to every possible form of humiliation and violence. Some of us have been sexually assaulted, but all of us have been tortured and continue to languish in prison.

Our Ordeals

I, Hajer Mansoor, was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment. My crime is that my son-in-law, Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei, dedicates his life to the promotion of human rights in my country. In October 2017, I was arbitrarily arrested, tortured and convicted on trumped-up charges of planting a fake bomb, a fallacy that the government also applied to my son and nephew. The only incriminating evidence they hold against us are confessions extracted under torture. My own ordeal is painful, but seeing my family undergo the same brutality is a different, more torturous, form of suffering.

I, Medina Ali, have been away from my six-year-old son for a year and a half now. I vividly remember the night I was taken. I was pulled out of my car by masked, armed men in a civilian car, who threatened me with death. During my detention, I was harshly beaten and threatened with rape. The injuries I sustained on my head have left their mark; a painful reminder of my powerlessness at the time. However, I will not allow an authoritarian regime to dictate my future. They may have charged and sentenced to three years in prison for harbouring a fugitive on coerced confessions, and silenced me from voicing my torture back then; but this will not stop me now.

I, Najah Yusuf, was sexually assaulted by the National Security Agency. Rape is a powerful weapon, as the victim’s shame is used to leverage their silence. I was tortured and humiliated for four, exhausting days until I gave them what they wanted; confessions for a crime I did not commit. My attempts to report the horrors of my sexual abuse to the prosecution and the judge fell on deaf ears. No one cared to listen. I only realised the extent of corruption in our justice system when I witnessed one of my abusers testifying against me in court. Soon after, I was sentenced to three years in prison on charges of inciting the overthrow of the regime, partly by criticising the Bahrain Grand Prix on Facebook. Last October, I lost the appeal against my conviction; my unjustified imprisonment goes on.

The Assault by Prison Authorities

When the UN Secretary-General and UK Parliament spoke about the reprisals against in September 2018, we felt hopeful that our torment would finally be heard and would soon end. This attention, however, prompted prison guards, led by the head of the prison, Major Mariam Albardoli, to humiliate, assault and isolate us. As I, Hajer, was rushed to hospital following the assault, I could not help but remember how in July, I paid a similar price for the UN’s and UK Parliament’s attention on my case.

The Punitive Measures

Since the incident, the prison authorities have been determined to break us; they have taken away our few remaining moments of joy, making our time in prison even more unbearable.

We spend 22 hours a day locked in our cell, but this solitude does not compare to the despair we feel for not having seen our families since the assault took place. For over three months, a glass barrier has been placed in the visitation room to separate the inmates from their families. It would break our hearts to see our children behind a glass barrier and not be able to hug them. We cannot accept to see our elderly parents, some of whom are bound to a wheelchair, in distress, without being able to offer them comfort nor solace. In the past, we resolved similar problems by going on hunger strike. This time, however, we were forced to end our hunger strike after five days in October without being granted our rights, as our bodies quickly became frail. While the requests of other inmates to see their families without the barrier have been addressed with resolution; this same right remains a luxury that we are not afforded.

The harassment we face remains severe; we have shed tears over the intimidation and discrimination we still face. Our personal belongings have been confiscated, including our family photos and books; we are not allowed to participate in the workshops organised for all the inmates in Isa Town prison, and the times allocated to meals are scheduled such that they conflict with prayer times. We thought the situation could not become any worse, but we were wrong.

A Policy of Isolation

Soon enough, the administration began punishing those who spoke with us, with the ultimate aim to isolate us completely. Back in December, an inmate and good friend to us was placed in solitary confinement for two weeks after I, Hajer, shared a packet of crisps with her. Another inmate was not allowed to smoke for a week after we provided her with the contact details of the National Institute for Human Rights, a local oversight body to whom we have the right to report our complaints. Most recently, another inmate in her fifties who suffers from arthritis was moved to another cell and forced to sleep on the floor after speaking with us.

This new policy of isolation has proven to be painfully successful. All inmates are progressively avoiding us, and we cannot blame them. If the price for sharing food or exchanging a few words with us is two weeks of solitary confinement or sleeping on the floor, we would probably do the same.

In the meantime, Bahrain’s human rights mechanisms continue to defend the abusive authorities and whitewash their crimes. The bodies we have reported to find no wrongdoing by dismissing all of our complaints. They even denied that we went on a hunger strike; such is the level of deception that they are practising.

Bahrain presents itself as progressive, but this is just a fantasy that some governments are all too ready to believe. Our ordeal coincides with the strengthening of political support provided to Bahrain from Washington and London.

As long as we remain capable of projecting our voices, we will ensure that our suffering is not rendered futile. We are certain that our fates can be altered. So we appeal to you in your capacity of High Commissioner to act on our behalf. Please, speak out about our ordeals and call for our release; don’t leave us here alone.

Yours Sincerely,

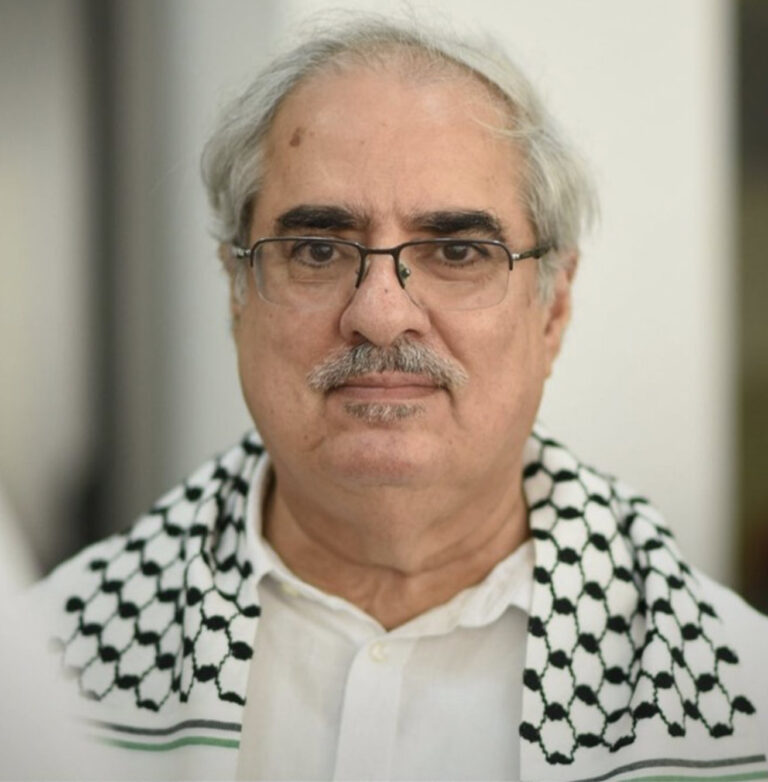

Hajer Mansoor

Medina Ali

Najah Yusuf