Bahrain: Boys Arbitrarily Detained in Orphanage

Families Left in The Dark

(Beirut, February 8, 2022) – Bahrain authorities are detaining six boys, ages 14 and 15, in a child welfare facility, the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy and Human Rights Watch said today. The authorities have not provided the boys or their families with any written justification for their weeks-long detention and have denied parents’ requests to be present during their interrogations and to visit their sons.

The boys, from the Sitra area, are being held on the orders of the public prosecutor’s office at the Beit Batelco facility in Seef district, which a government website describes as an “institution … for children of unknown parentage, orphans and children of broken families up to the age of 15.” The children’s alleged offenses appear to have occurred in December 2020 or January 2021, when they were 13 and 14, based on the boys’ recollections of their interrogations. A statement by the Office of the Public Prosecution alleges they threw Molotov cocktails that damaged a car near a police station.

“Last year Bahrain touted its legal reforms for children, but locking up children in an orphanage instead of a jail is hardly an improvement when their detention is arbitrary in the first place,” said Bill Van Esveld, associate children’s rights director at Human Rights Watch. “The treatment of these boys is a test of Bahrain’s respect for children’s rights, and so far the authorities are failing.”

Bahrain’s 2021 Restorative Justice Law for Children sets the minimum age of criminal responsibility at 15 but permits authorities to “place the child in a social welfare institution” for renewable weekly periods “if the circumstances require.”

The children, from three families, were first summoned by the public prosecutor for questioning in June 2021. Some were questioned at least eight times, and sometimes detained overnight at a police station, before their arrests, parents from two families said. “We received a call from Sitra police station to bring them, and then from there they took them to the Office of the Public Prosecutor without letting me go with them,” one family member said. “I was never allowed to be present in the interrogations. They said I needed to have permission from the prosecutor. We didn’t even know what the [alleged] crimes were.”

Another boy’s father said the allegations changed over the course of the interrogations, based on what his son told him: “First it was about burning a tire, then it was attacking a police station, and then it was throwing a Molotov cocktail. My son told me that when they asked him a question they screamed at him not to lie. The father said he told the director of the Sitra police station, “‘These are kids, don’t destroy their future,’ but the director said, ‘Your son is a vandal.’”

On December 27, the Public Prosecution summoned five of the boys and arrested them. The sixth boy was arrested on January 9.

The children were first transferred from the police station to Dar Al Karama, which a government website describes as a “care home for beggars and the homeless,” then transferred on January 5, to Beit Batelco. Their detention has been renewed by the prosecutor weekly, most recently on February 2. “Every time they renew their detentions we feel shocked,” another family member said in a televised interview. “We are not able to offer a life with freedom and peace to our children.”

One boy’s father traveled to both locations and asked to see his son but was refused without explanation. He appealed to the prosecutor and the attorney general’s office for his son’s release, “but they ignored it,” he said. “They say, ‘Look, they are in a care center,’ but they allow him only one telephone call [per week], they don’t give him any [family] visits. Effectively he’s a detainee, the doors are shut on him.”

Another man said the authorities at the two facilities told him that family visits were prohibited “because of orders from the Office of the Public Prosecutor.” The children are allowed one 10-minute phone call each Monday.

A defense lawyer for five of the boys said they “are accused of obtaining and manufacturing Molotovs, but it is unclear if there is a specific incident attributed to them, or [if] they [are accused of having] used them.” The lawyer has not been informed of the legal basis for detaining the children or why they are being detained at the Beit Betelco orphanage. At their hearing on January 24, he said, the boys were taken to court wearing t-shirts and were visibly cold, but a social worker and a judge did not respond to concerns that they needed warmer clothing.

It was not until February 1 that the Office of the Public Prosecution released a statement about the case, which the rights groups reviewed. It said that prosecutors had ordered the children detained for allegedly throwing Molotov cocktails at Sitra police station, which damaged a civilian car, and that their detention had been extended pending their referral to the Child Correctional Court. One boy’s father contacted the two rights groups to share the statement, which he said provided more information about the case than the families have received.

Bahrain should revise Law No. (4) of 2021 Promulgating the Restorative Justice Law for Children and their Protection from Maltreatment to clearly provide for a child’s right to have their parents and a lawyer present during interrogations, and to challenge their deprivation of liberty, the organizations said. Bahrain should also revoke the law’s determination that children who participate in unlicensed public assemblies may be considered “endangered” and deprived of their liberty.

International law prohibits detaining children except if necessary as a last resort and for the shortest appropriate period, due to the inherent harm and risks of abuse. The authorities have not explained why it was necessary to detain children who had repeatedly appeared when summoned. Their detention also contradicts guidance from UNICEF for governments to impose a moratorium on detaining children during the Covid-19 pandemic.

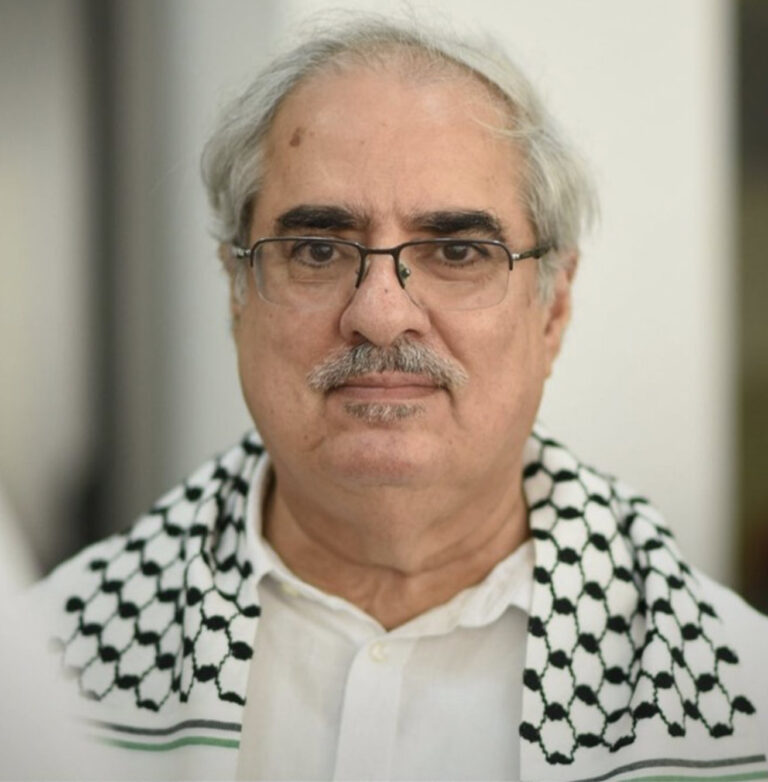

“The reality is that if the government of Bahrain doesn’t like your children, they can be taken away and locked up and you won’t even be told why,” said Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei, advocacy director at the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy. “Bahrain’s allies should demand the release of these six boys – even if they’d prefer not to discuss human rights, harming children undermines Bahrain’s stability.”

For more Human Rights Watch reporting on children’s rights, please visit:

https://www.hrw.org/topic/

For more Human Rights Watch reporting on Bahrain, please visit:

https://www.hrw.org/middle-

For more information, please contact:

For Human Rights Watch, in Athens, Bill Van Esveld (English): +1-917-535-3647 (mobile); vanesvb@hrw.org. Twitter: @billvanesveld

For the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy, in London, Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei (English, Arabic): +447445382565 (mobile); sayed@birdbh.org.